Green Infrastructure: The City perspective

Part I of this report focused on the basic concepts of green infrastructure (GI) and New York City’s progressive adoption of these concepts to address a growing range of challenges. It also highlighted the work of the Gowanus Canal Conservancy (GCC) as an example of nonprofit and community involvement in this effort.

Part II will focus on efforts by the City (i.e. NYC government) itself, especially through the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), and the accelerating battle to address climate change, which is further stressing an already-overburdened stormwater and wastewater system.

Water

The story of New York City is very much a story of water. Founded and developed as a seaport, where goods flowing down the Hudson River from the interior – first from the lands of upstate New York and then from further west through the Erie Canal as well – were shipped off to the world and, increasingly, where goods and people flowed into the ever-expanding country from overseas. The city and its surroundings were also literally fed by the waters, especially by the oyster banks that grew in profusion around the islands and estuaries.

However, access to fresh water and disposal of wastewater have also shaped the city. As described in various histories (DEP’s or others like this from the Smithsonian Magazine), it took decades of living with disease and inadequate infrastructure for New York to finally begin seriously addressing its needs. This eventually resulted in one of the greatest water supply systems in the world. Unfortunately, it drained into a less visionary wastewater system that addressed the problem of sewage flowing through the streets by channeling it directly into the surrounding waterways. Even as the City began building infrastructure to treat this waste, massive amounts continued to flow into the waterways surrounding the city both from areas not connected to treatment facilities and when heavy rainfall would overwhelm the parts of the system carrying both rainwater and sewage, causing Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO). Over time, this poisoned marine life, killed off most of the oyster beds, and made the waters surrounding the city too dangerous to swim in or fish from.

As related in Part I of this report, the problems caused by this began to be seriously addressed following passage of the 1972 Clean Water Act, resulting in a rebirth of the natural waters around the city. Unfortunately, the problem of CSO remains and has been exacerbated by a growing population along with a changing environment that places increasing stress on this wastewater system. As noted, green infrastructure has come to play an important role in responding to all of these challenges.

Evolving Efforts

Initially, as can be clearly seen in the 2008 PlaNYC Sustainable Stormwater Management Plan (SSMP), the focus was on water quality. Following Superstorm Sandy in 2012, however, emphasis shifted and grew to include coastal inundation. This further broadened to encompass cloudburst events even before the city was struck by Hurricane Ida in 2021.

The City had undertaken a number of separate initiatives to increase greenery and address problems caused by the densely built environment, such as the Greenstreets Program in 1996 and the MillionTreesNYC campaign in 2007, which was part of a wide range of PlaNYC initiatives. These many scattered efforts came together in the 2008 SSMP, “the City’s first comprehensive analysis of the costs and benefits of… alternative methods for controlling stormwater” (SSMP, p. 7). This plan was updated in 2011 and a progress report issued in 2012. Its principles continue in subsequent documents, most recently in the May 2021 New York City Stormwater Resiliency Plan (SRP) and October 2021 report following Hurricane Ida, The New Normal: Combatting Storm-Related Extreme Weather in New York City.

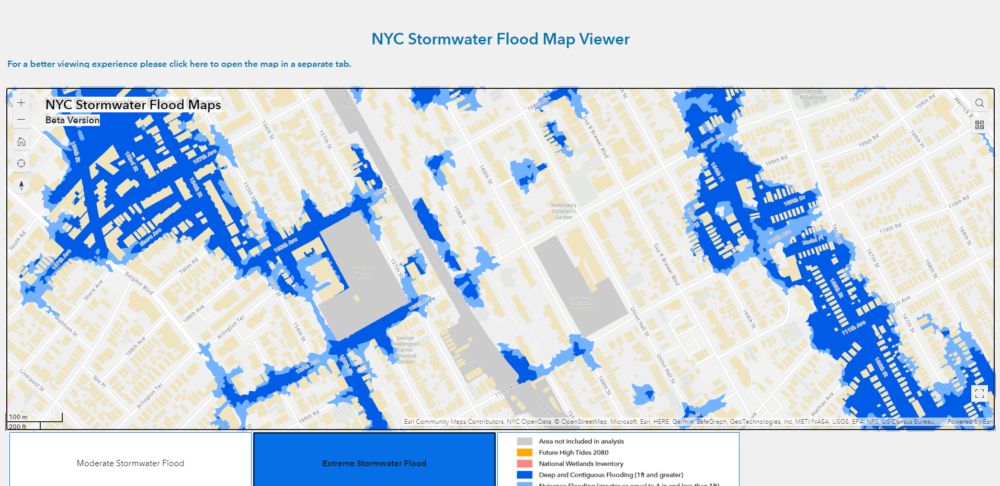

The SRP is the product of the 2017 Stormwater Resiliency Study, undertaken by staff from a broad array of City agencies along with external consultants and academics. In 2018, the New York City Council passed Local Law 172, which mandated the creation of maps showing anticipated flooding resulting from the changing climate along with a plan to prevent or mitigate this flooding.

New York City Stormwater Flood Map

Although the City recognized the potential impact of increased rainfall, among other adverse consequences of climate change, and moved to prepare for those through better data collection and planning and through better public awareness and information, nature ended up moving faster than the City could prepare for it. Hurricane Henri dumped almost two inches of rain (1.94”) on August 21st, 2021, breaking rainfall records, and was followed closely by Hurricane Ida on September 1st, which pummeled parts of the city with over three inches of rain in one hour and over seven inches before it ended 24 hours later. In New York City alone, 13 people died because of Ida, 11 of them in basement apartments in Queens.

According to DEP, the flooding closely tracked what the maps had predicted, even though those predicted rainfall amounts were given a very small statistical chance of occurring in any given year. Unfortunately, the planned system of flood monitors and warnings has also not yet been built, so there was very limited ability to track what was happening or warn residents who might be in danger.

On October 4th, the City released an update on its efforts in the wake of these two storms, The New Normal: Combating Storm-Related Extreme Weather in New York City, mentioned above. Among other things, this report contained commitments to:

Projects / Practices

Looking at DEP’s green infrastructure map, it’s clear the majority of projects so far have been built in Queens and the Bronx. While bioswales and other green infrastructure projects have been built across the five boroughs, most of them, and some of the largest and most advanced projects, have been undertaken in the areas of Queens that were already under-sewered and susceptible to flooding. These areas are also in sewersheds feeding into some of the most polluted bodies of water around the city. According to the DEP, green infrastructure is being utilized here as a buffer, buying time to upgrade the inadequate grey infrastructure serving the area. However, given the scale and nature of the projects, these will clearly become permanent parts of the landscape. When asked why these boroughs have received the most attention, DEP responded that besides the fact that much development in these areas happened before adequate wastewater systems could be installed, part of the reason is also geography. Manhattan has very little GI but also little problem with flooding. A lot of this certainly has to do with its topography, as a narrow island where water tends to flow quickly off to one side or the other and into the surrounding rivers. It, like much of Brooklyn, has also been a heavily built-out urban area for well over a century so has had more time to develop its infrastructure. Queens, on the other hand, was largely farmland until relatively recently, and much of it consists of wetlands with less-than-ideal drainage, where flooding is likely to occur. The Bronx and Staten Island were also built out later, with infrastructure inadequate to the level of development that occurred over time. Staten Island has benefitted from the Bluebelt systems that continue to be created there since 1990; and while less than the others, Brooklyn has numerous projects, mainly concentrated in its northeast section adjacent to Queens, where some of the worst flooding occurs.

A map in the 2008 Sustainable Stormwater Management Plan showing complaint levels for sewer backups clearly indicates southeast Queens is one of the three worst areas in the city, and the only one that’s inland and not also affected by inflow issues. Inadequate sewer capacity is one of the main factors cited by Alan Cohn, Managing Director, Integrated Water Management, for DEP’s focus on southeast Queens for green infrastructure development. The 2020 NYC Green Infrastructure Annual Report also references this (p. 48), saying that over the last 10 years the area has had the most complaints in the city.

Beyond numerous right-of-way (ROW) bioswales and other smaller “practices” (to use the DEP term for these green infrastructure installations), there are major projects planned, underway, or completed in St. Albans, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) South Jamaica Houses complex, Roy Wilkins Park, Conselyea Park, Baisley Pond Park, and through the neighborhoods surrounding them.

In the St. Albans neighborhood, DEP has undertaken a project to regrade certain streets to diversify rainwater flow and relieve overwhelmed sewers while also installing a number of bioswales to help divert and retain water before it reaches the sewer system. According to the 2020 Green Infrastructure Annual Report, over 100 ROW practices had been built in the St. Albans and Cambria Heights neighborhoods by that point, although DEP says they are currently in the design phase to increase this number.

A large bioswale was installed in Roy Wilkins Park. As part of this work, DEP and DPR installed catch basins to divert stormwater from Merrick Boulevard into the bioswale. Underground storage chambers (drywells) within the area of specially modified soil and plantings further help absorb and diffuse rainwater. Along with this, the pond in the park was deepened to serve as a bioretention basin, with any excess water then overflowing into the sewer system. The underground storage can handle approximately 761,000 gallons of rainwater annually, with the pond providing further capacity. Only the bioswale is noted on the map.

Bioswale (with inlet in the distance) at Roy Wilkins Park

Newly enhanced pond at Roy Wilkins Park

A major project was launched in 2018 to address increasing flooding around NYCHA’s South Jamaica Houses in Queens as part of the City’s Cloudburst Resiliency Master Plan. This project has been planned to utilize blue-green infrastructure to not only alleviate flooding, but also to provide social and environmental co-benefits to the community, and this has been developed through a series of public input events (“charettes”). A pilot project involving part of the campus is being undertaken initially, and it is the first such effort on NYCHA property. Construction should begin in about two years, according to DEP. NYCHA and DEP partnered on this project with Marc Wouters | Studios to carry out the necessary studies and planning, which resulted in the South Jamaica Houses Cloudburst Master Plan 2018. The project is based on the Cloudburst Resiliency Planning Study carried out by Ramboll and completed in 2017. Eventually, the plan is to extend green infrastructure improvements through the surrounding neighborhoods.

South Jamaica Houses consists of 27 low-scale apartment buildings spread over about 23 acres of wooded land on eight blocks, intersected by walkways, and is home to about 2,700 people. A study in 2018 examined how the site could be configured to divert and retain stormwater most effectively in order to reduce flooding in the area as well as flows to areas downstream, relieving pressure on that wastewater infrastructure. A plan for developing various types of green infrastructure to accomplish this was developed over time through collaboration among DEP, NYCHA, design firms and consultants, and residents of the community. A design charette and series of workshops were held that brought an already-active group of community gardeners and other residents to give input on what they would like to see done. Given the fact that almost every element of a green infrastructure solution (gardens, basketball courts & playgrounds, open areas, etc.) has secondary benefits for the community and is used by them, as well as the fact that, as noted in Part I of this report, volunteers to maintain the assets are vital to their continued effectiveness, community buy-in like this is critical.

Site of a planned bioswale at South Jamaica Houses

Basketball courts currently at South Jamaica Houses

Issues

Two issues for DEP that will require ongoing attention are monitoring and maintenance. In discussing how the current assets performed during Henri and Ida, DEP noted that they seem to have performed as expected, but it is hard to quantifiably substantiate this due to a lack of monitoring or measuring capability. That is something that will need to be addressed in order to better understand how projections are holding up in real-world conditions and work toward optimal designs. Here, again, programs that are in the works were not able to be rolled out in time for these major tests of the system and more time is necessary to get these up & running. On top of this, the City faces the same challenges that the Gowanus Canal Conservancy (GCC) noted in securing cost-effective, easy-to-use equipment to monitor performance. In the absence of a technology-based monitoring system, maintenance needs for NYC Rain Gardens are currently tracked through maintenance data kept by the DEP crews supplemented by any reports that come in through the City’s 311 system.

The City has been developing a fairly simple flood-monitoring system that it has begun to deploy, but the needs there are far less complex than what is required to understand the performance of something like a bioswale. FloodNet (also see here) is planned as a monitoring and early warning system for residents when rising water is detected from hurricanes, tidal flooding, or cloudburst events. This system can help track whether GI is successful in preventing or alleviating flooding, although it cannot fulfill the needs outlined by GCC for supporting bioswale maintenance. The FloodNet system is being developed as a collaboration among academic research institutions and the NYC Mayor’s Office of Climate Resiliency and the Mayor’s Office of the Chief Technology Officer.

Also, when asked about how maintenance is performed, referencing the information related by GCC reported in Part I, DEP pointed out that while volunteers are critical to keeping GI functioning effectively, there are limits to what they can do. DEP has worked with DPR to model their volunteer stewardship programs and has conducted some limited testing of this concept. However, these efforts are tough to scale up and currently, once the “warranty” period concludes for any GI practice, responsibility is transferred over to DEP’s in-house maintenance team, which is hiring more workers as the workload grows. They currently have about 4,000 practices overseen by around 100 people. Moving forward, though, with over 11,000 practices now built and many of those scheduled to be transferred over in the near future, it’s hard to see how DEP could hire enough staff to care for all of the GI that is projected to be developed without a large cadre of volunteers to help with at least the basic ongoing maintenance needs. However, a central issue is the inability of volunteers to deal with issues involving railings, stones, pruning, and other more difficult tasks. Community groups that engage in maintenance would also need equipment and insurance. Nonetheless, DEP has been training and onboarding people and groups in several neighborhoods to assist with the work.

GI maintenance for assets on NYCHA property is conducted by DEP. However, DOE and DPR handle any assets on their properties.

The latest information currently available is in the 2020 Annual Report, with maintenance (including monitoring) and stewardship highlighted on pp. 45 & 46. A new 2021 report is due to come out soon.

Conclusion

As a coastal community of 8.5 million people, situated almost completely on a number of islands, and serviced by infrastructure that is, in some cases, well over 100 years old (if not almost 200), New York City faces serious challenges simply owing to its size and location. Add to this budgetary constraints and the difficulties of conducting any sort of construction activity in such an already densely built environment and the challenges facing DEP and the City overall can clearly be understood to be quite daunting. However, through ongoing efforts led by many dedicated professionals and aided by volunteers and community groups, progress is being made to identify and address the serious issues arising from climate change on top of chronic deficiencies with which the people of New York have wrestled for hundreds of years. Through both inflow and outflow management strategies, the City is racing to get ahead of a rapidly-changing situation.

Matthew Gillam

Senior Researcher

April 21, 2022