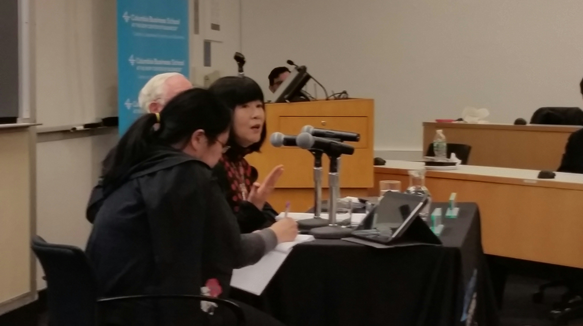

It was a rare opportunity to hear from Professor Yukari Fujimoto, a professor at the School of Global Japanese Studies, Meiji University in Tokyo. She is an expert on cultural matters in Japan, in particular on the voluminous amount of Manga and Anime that is so characteristic of Japanese literary scene. As a professor, she has expanded her reach into trans-national comparisons and the talk she gave at Columbia University’s Center on Japanese Economy and Business was a delight to listen to.

First, Professor Fujimoto described the size of the Manga/Anime market. That they are popular all over the world goes without saying. That, of course, is true about all comics and Anime but, in Japan, it is especially so. The market is a ¥460 billion yearly concern (approximately $4.6 billion). The cell-phone market itself is about $1 billion. At its height, in the 1990s, print Manga was worth about $6 billion. The sheer volume of Manga books and magazines is incredible – 918 million. It comprises about 40 per cent of all published works in Japan. The annual revenue from Manga alone is ¥3.76 billion. Part of the reason for that is the cheapness of the product. Two hundred pages costs on average about $4 to $5. To put it into perspective, American comics account for only 2 to 3 per cent of printed works (in France it is about 7 to 8 per cent). Interestingly, half of all published Manga is for adults (18+) and 60 per cent of all revenue comes from this adult market.

Manga, generally, is published in serial form (or as a one-off and self-contained story). That was a favourite form of literature in the West during the 19th Century. The success of The Pickwick Papers, by Charles Dickens, serialised in a monthly publication, in 1836 led to a great number of other serialised novels. In Japan, the Shonen Magazine (known as Shonen Sunday) began its weekly Manga stories in 1959. The Magazine created ‘Big Comic’ for men in 1968 and the weekly Manga action in 1967. But, Shonen aimed at the young adult (junior high to high school students). This division of targeting the magazines for men and women has a long pedigree. Women magazines date back to 1902 and men magazines back to the 1880s. Nowadays, there is difference between the style of story writing and drawing for men and women. Manga for men tends to be designed as if it were viewed as a film, panels giving the impression of movement. For women, the layout is much more multi-layered.

A number of reasons were why the serial form was chosen as the preferred method for story content. First, the theme of the story can be developed with much more complexity. Second, and more important, the writers can take into account the reaction of readers whilst the story is being built. Then, the serial can produce a long story that has ups and downs. Since most magazines will limit the serial to one chapter, there are a number of different stories to view and build up a readership for new authors.

There is an essential difference between the creators of Manga in Japan and those who work on Comics in the United States. The artwork is done by the artist alone, not a division of labour as in the United States among various people. The artist directs everything in Japan, though he may have assistants. The assistants, however, work at the direction of the artists. In Japan, the copyright remains with the artist, who usually works out a royalty fee arrangement for the published circulation of the finished product. Bestsellers can sell over 320 million copies, as compared with the United States where bestsellers will perhaps reach about 130 million copies.

This was an informative and interesting talk.